By Shweta Mishra

Dia de los Muertos — October 31, 2009

Fine nighttime rain shimmered amid headlights bobbling into the yard. Nine years after becoming undocumented, Esteban Ginocchio-Silva was throwing a party.

Bare-chested, wearing a pink mask emblazoned with a cross, the 5-foot 21-year-old cracked his knuckles, rolled his neck and broke into a mix of yodels and hoots, spirit fingers raised and body spasming. This was his stage entrance for El Dia de los Muertos. He was a luchador.

“I like parties like this because our traditions in Peru celebrate life,” he said. “Quinceañeras, cumpleaños, bailes, polladas — dances, home-made fried chicken and beer offered to the whole neighborhood. Community was how things rolled.”

Except for the beer keg, this celebration was unusual for downtown Carrboro and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. In the affluent, well-meaning but neatly self-segregating college towns, Esteban had brought together Latino, black, Chinese, Australian, South Asian, British and Greek young adults with disparate class backgrounds. Only a quarter of the guests were white suburban Americans. But the conviviality was just human. Frida Kahlos, skeleton brides and Che Guevaras streamed in, not navel-baring nurses, but underneath they were just excited young women. In the kitchen, transsexual grannies with British accents cradled screwdrivers and chomped on traditional Mexican bread of the dead, flashing smiles from under their bonnets, lifting their floral dresses too high. Partiers on the veranda offered sugar skulls, tea-lights and flowers to Michael Jackson’s luminous death altar.

Put on a Happy Face

Amid the international throng, Esteban’s golden face, shrewd bright eyes and Cheshire Cat smile belied the skeletons in his closet. Researchers at the Department of Public Policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that immigrant Latino youth, particularly those without papers, suffered from clinical depression and anxiety at statistically higher rates than their white and black American counterparts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention corroborated these results by finding that Latino youth also planned and attempted more suicides per year. Why so distressed? The UNC-Chapel Hill study pointed to “high poverty levels prior to migration, stress during migration, and racial and ethnic discrimination upon settlement in the US.”

Esteban was not just an immigrant. He belonged to an even murkier subset of this high-risk category. Once the US Immigration and Naturalization Service sent vital paperwork to the wrong address right before the deadline, he and his family had become disabused of any hope they had entertained in the American Dream. No Mother of Exiles could be expected to wait for them by any golden door, with any mighty torch in her hand. The pleased face Esteban put forward testified to his unusual resilience and tenacity. When Halloween ended, he quietly resumed studying, not at a university of his choice but Durham Technical Community College, which he paid for himself by working full-time at Mediterranean Deli, a popular downtown restaurant. It was his third year doing this, and he was dog-tired. But he had dreams he had to fight for.

“I always wanted to be a business owner,” he said. “I wanted to be my own boss, you know, the whole romanticized aspects of the American dream. I thought a degree in economics would be the way to get there.”

Great Expectations — 1988 – 2000

At first no one had thought about moving to the United States. Three months after Esteban’s birth on Dec. 9, 1988, his family settled in Chosica, a promising city near Lima, Peru’s capital. Enrique Ginocchio Reeves got a job preaching at Bethel Baptist Church. He and his wife, Fernandina, enrolled their son in a private Christian school. Esteban flourished.

“But it sheltered me from getting a more real experience of the world,” he said.

While three written warnings meant a rap on the rear with a paleta, that never actually happened. It was only when he played hide-and-go-seek on the streets that he saw kids whose teachers did beat them, and others who spent schooldays begging for food.

“I saw homeless children basically spacing themselves on top of cars at stoplights to clean their windshields, and risking either getting run over or not getting paid,” Esteban said.

He saw brick houses next to cardboard shacks, people with electricity and others without drinking water.

“I could definitely tell the difference at a young age, and that was part of my upbringing,” Esteban said. It made him compassionate when his own fortune turned. When the specter of joblessness caught up with Esteban’s parents, Enrique turned to church friends who lived in North Carolina. In 2000, the family moved to Graham, NC, with a tourist visa. Enrique became a preacher at The Church of Nazarene. Esteban and his sisters learned English.

The family’s prospects withered when the US Immigration and Naturalization Service sent paperwork to the wrong address one day before the deadline.

Revision of the Future — 2010

But Esteban didn’t dwell in the past long.

He said he held himself with dignity and hope rather than cowering as an undeserving fugitive because his philosophical mind recognized a self-serving moral relativism in American law and history, and that individuals involved were just pawns, exonerated or deported by circumstantial details. He saw through the sanctimonious bureaucratic double-talk of immigration politics of the day into the messy heteroglossia of America’s real past. He and his sister Loida analyzed their undocumented presence in relation to that of John Smith’s settlers in Powhatan territory in 1609. Unlike the Jamestown settlers, the Silvas had not violently raided food stashes of tribes, nor planned to plant their own flags on a bleeding ground.

It was with this outlook that, in the summer of 2011, Loida changed her Facebook profile picture to Asheville Mountain Express cartoonist Randy Molton’s caricature of an angry skinhead next to an Indian chief with a crown of feathers.

“Protests should’ve been made about immigration years ago!!” said the skinhead in his speech bubble.

“Oh, at least a few centuries ago!” said the chief.

That is, Esteban thought, before the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Indian Removal Act, Trail of Tears. Before his ancestors, or at least genetic equivalents, were displaced from their traditional lands.

Of course, Esteban’s historian logic was absent in discussions among congressmen, whose composite face as digitally calculated by artist Rebecca Lieberman and developer Matthew Skomarovsky was that of a masculine, middle-aged white man with a receding hairline, the stereotypical son of colonial America. For this white face of congress, it seemed irrelevant that after the American Revolution and before the 1800s, the United States’ first immigrants — perhaps the congressmen’s ancestors — were themselves undocumented. That in the 1600s and 1700s, all settlers were foreign immigrants and fugitives who crossed myriad borders of myriad indigenous nations.

Esteban said that it was this amnesia of privilege that had allowed congress to glibly quibble over immigration reform for 11 years.

The DREAM Act, or Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, was a bill that would grant undocumented minors a pathway to citizenship contingent on higher education or military enlistment. If it had been passed in 2006, when Esteban graduated from high school, it would have allowed him to apply to universities and get private scholarships.

The Yellow Brick Road with an Impasse

Esteban’s hard work at Durham Tech paid off when the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill admitted him as an undergraduate transfer in fall 2010. But it was a Pyrrhic victory as the Public Ivy classified him as an International Student, which meant he had to shell out nonresident tuition and fees of $12,640 per semester instead of the $3,333 for other state-dwellers. His status also meant ineligibility for university scholarships and the Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

Learning of this, Esteban’s boss thought, why not just marry an American citizen? Esteban could get financial aid, a driver’s license, a legal work permit.

“When I came here, I married a friend in three months exactly,” Jamil Kadoura said. “It used to be easy, but I guess then terrorism happened.”

Regardless, Esteban’s preferred solution was the DREAM Act. On May 18, 2010, he and four other local undocumented youth formed the North Carolina DREAM Team. One of the group leaders was Viridiana Martinez, a Mexican-born undocumented activist profiled in the Al Jazeera documentary “Activate – The Dreamer.”

“We met at Noodles & Company and made a plan to fight,” she said. “Esteban was there and Loida and Rosario and me and Manuel. We knew that we, the youth, had to sort of take more of a lead role in what was already happening, this whole talk of immigration reform. The Dream Act in particular because that was something that existed. It was a bill that was there since 10 years ago and we knew we needed to be at the forefront.”

Unlike the rest of the group, Esteban remained “in the shadows,” unwilling to publicly disclose his legal status, because he felt he had too much at stake.

“I knew what he was up against,” Viridiana said. “Having to work to pay all of this money for school, and activism on the side. But he was there. He wanted to do it, so that’s how NC dream team got started.”

Later that summer, Viridiana, Loida and Rosario led a strike in Raleigh.

“My own sister Loida decided to starve herself in the summer heat,” Esteban said. “Right in front of Senator Hagan’s office as long as she said no to the bill.”

The strikers stopped after 13 days. Esteban’s sister had been hospitalized for a heat stroke.

The Kindness of Strangers

Senator Hagan voted no anyway.

It seemed that, ultimately, no amount of activism made a difference in Esteban’s daily life. After the hoopla and heroism, he had to turn to his boss again. Influenced by a childhood in the Middle East, where his and his family’s survival as Palestinians had depended on the benevolence of the Red Cross, Jamil had a charitable spirit that was renowned in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. He thought Esteban was a nice kid, sharp, so he gave him an interest-free loan for half the amount Esteban needed to take two classes. Esteban paid the difference with personal savings and eliminated his debt within the semester. He also worked to pay his rent and bills. There was little time in his day to eat and none to study, and after the first term, he gave up. “I didn’t really have the wherewithal to push myself and needed a break for my own sanity,” he said. Anyway, there was no more money.

Go West, Young Man, and Grow Up with the Country — March 20, 2011

On the third floor of a colonial house in Echo Park, Los Angeles, Esteban, now 23 years old, lay awake on a mattress in a walk-in closet. Thunder cracked and rain beat the gabled roof. Wind blustered through the gaps in the windows.

Esteban could hear his hosts, five young gay Filipinos, laughing downstairs. He was here because he had decided, after a year of working himself to the ground to pay for two classes, to quit and leave.

“It never went through my mind to really move west,” Esteban said. “It was more like a rebellion against my circumstances.” He had found his hosts on a couch-surfing online forum.

Though he’d originally hoped to adventure on a Greyhound from North Carolina to New Orleans, and then north to California, he decided flying would eliminate risks of hitting migrant checkpoints. He arrived in Los Angeles on the first morning of spring and what would be California’s wettest day in 2011, a fluke for The Golden State. He got drenched at the bus station. That day there were also flash floods, mudslides, power outages. Stubborn marathon runners were rushed to emergency rooms for hypothermia.

Of course, after his cross-country flight from North Carolina, the pressing problem was not weather but whether this new land would also strangle his dreams.

The day before, two dozen white supremacists had rallied in Claremont, CA. Bald young men held up swastika flags and wore battle uniforms. The southwest regional director of the National Socialist Movement, Jeff Hall, decried California’s apparent friendliness to illegal immigrants.

Back in Chapel Hill, Helen Martyn, an elderly Los Angeles native, came to Mediterranean Deli for dinner one day. With glittering eyes she said Mexicans crossed over just to demand free services and hate her country.

“They come here to spit on us,” she said.

So any distance away from home, the anger shined from sea to shining sea. Esteban would leave for Seattle tomorrow.

Motherland — 2014

Esteban’s parents were now in Peru, irrevocably, and he thought of them. He recalled his far-flung childhood, when anything seemed possible, when he didn’t know he was poor or an alien.

He remembered the high, dry, thin air of his rural birth village in Jauja Province, 11,000 feet above sea level. Fruiting Blue Gum eucalypts with silvery bark and tassels of flowers. Gnarled and squat, red-barked Queñua evergreens that broke through crags.

He remembered chewing coca leaves just like European tourists did to combat altitude sickness.

From a distance, he could still see crop lines on Jauja’s flat fields, their underbellies clotted with potatoes. The sky was wide and the Andes visible on the low, distant horizon. He remembered summer hail and rain rattling the tin roofs of adobe houses. The incense of earthen hearths blazing village-wide.

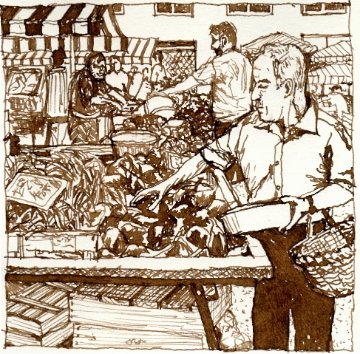

When he thought of the Mercado Municipal, Jauja’s open-air bazaar, he smelled the rust and iron of congealing blood. From morning till dark, raw lamb heads hung on hooks, men and women in traditional garb stirred up lamb head stew and vendors roasted lamb chops and suckling pigs. Herds of livestock bleated, brayed and shed their sour, loamy funk. Timber and native crops like quinoa and potatoes bumbled along on the backs of donkeys.

He marveled at the potatoes. He said he ate 15 varieties, small and rich as egg yolks to graceless as Russets from Idaho. He remembered the olluco, an indigenous tuber with the consistency of radish but long, yellowish and flecked red. He laughed to recall its tastiness.

Fourteen years and 3,278 miles after those market aromas, his memories persisted. Peru was the last place he felt like a visible human being. Even though he had lived in America for most of his life, it had never seen him as its own.